Gearboxes provide torque multiplication, speed reduction, and inertia matching for motor drive systems. Servo systems, in particular, require gearboxes that not only deliver high torque and low inertia but also offer high precision and rigidity.

There is a type of gearbox that meets all these requirements while boasting a relatively long service life and low maintenance needs—the planetary gearbox.

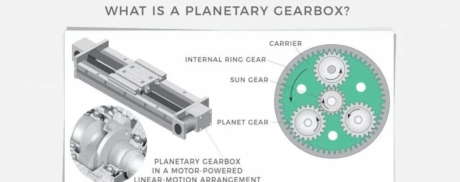

A planetary gearbox is an enclosed gear transmission device containing multiple gears. In fact, planetary gear sets are likely the most common configuration in integrated gearboxes.

Planetary gearboxes connect directly to precision motors either via couplings or, increasingly, through direct integration by motor manufacturers.

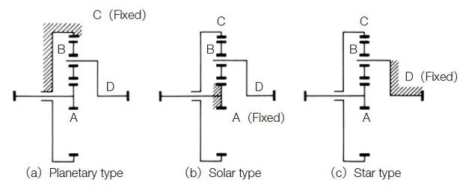

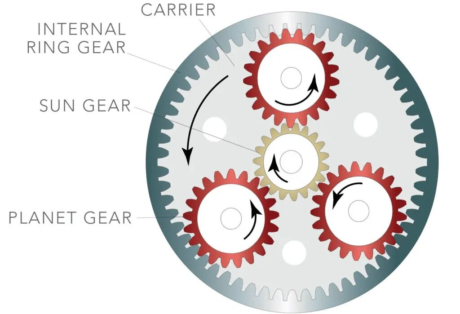

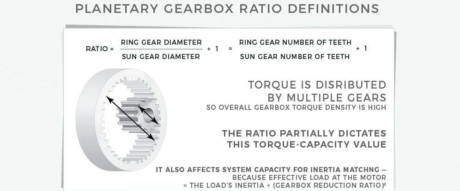

More specifically, the simplest planetary gear set consists of three gear subtypes. Planet gears rotate around a stationary sun gear, while an internal ring gear (typically a fixed gear machined flush with its inner surface) houses the individual planet gears.

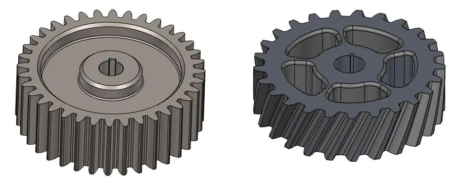

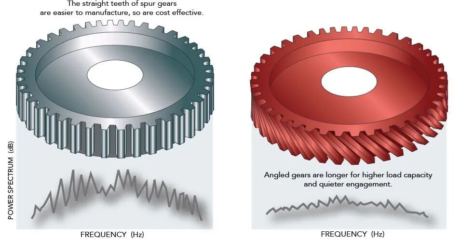

It is important to note that planetary gearboxes can be manufactured with spur gears or helical gears. Spur gears have a helix angle of zero and thus do not generate axial forces; therefore, bearings in spur gear planetary gearboxes only serve to support the gear shafts.

In contrast, helical gears have a helix angle between 10 and 30 degrees, which causes them to produce significant axial forces. Bearings used in helical gear planetary gearboxes must be able to withstand these axial forces. (A larger helix angle results in greater axial forces, but also provides higher torque capacity, lower noise, and smoother operation.)

Note: Planetary gearboxes can use either spur or helical gears. While spur gears typically have a higher torque rating than helical gears, helical gears operate more smoothly, with lower noise and higher rigidity—making helical gear planetary gearboxes the preferred choice for servo applications.

It should be noted that the angled tooth contact of helical gears generates thrust, which the machine frame must counteract.

Planetary gear assemblies handle loads in a unique way, making them particularly suitable for applications requiring strict rigidity, dynamic loads or frequent start-stops, low inertia and high torque density, and designs targeting high efficiency.

Unlike most standard gear drives, which transmit the full load of the shaft through a single gear mesh, planetary gearboxes typically have at least three mesh points engaged simultaneously. The inherent balance of these mesh points facilitates optimal lubricant distribution, allowing planetary gearboxes in certain designs to withstand input shaft speeds exceeding 10,000 rpm.

When a gearbox is added to a drive system, the speed transmitted from the motor to the driven component is reduced by the gear ratio, enabling the system to better utilize the speed-torque characteristics of the servo motor. Planetary gearboxes can withstand extremely high input speeds, with standard designs offering reduction ratios up to 10:1, and high-speed designs reaching ratios of 100:1 or higher.

The tight tolerances and low backlash (high torsional rigidity) of planetary gearboxes help minimize backlash, thereby improving the precision of the gear-motor assembly—this is especially critical in applications requiring driven positioning tasks.

There are multiple methods for selecting and sizing planetary gearboxes. The first method is to choose a fully integrated gearmotor. The second is to use a traditional configuration, where sub-assemblies are specified individually. For the latter, it is first necessary to analyze the application’s duty cycle and motion profile.

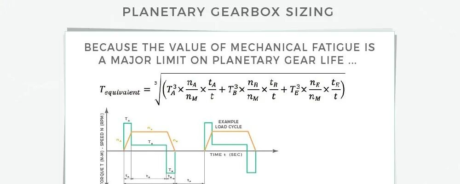

For highly dynamic applications, sizing requires the use of equivalent load values, which can be calculated using the formulas shown here. Note that unlike the root mean square (RMS) values used in motor sizing to quantify thermal and current limits, mechanical fatigue is a major limiting factor for planetary gearboxes—similar to the L10 bearing life rating.

The rated torque of the planetary gearbox must meet or exceed the equivalent load torque to drive the load continuously. Why is this important? Because the rated torque, motor model, and gearbox reduction ratio ultimately determine which gear combinations are suitable for a specific application.

In addition to this value, maximum peak torque (i.e., the torque an application may require during emergency stops) is another factor to consider. Typically, this value indicates the number of cycles a planetary gearbox can withstand before failure.

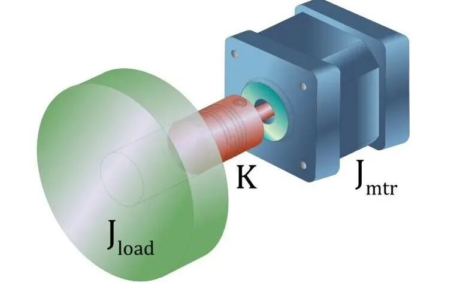

The kinematic characteristics of planetary gearboxes ensure reliable lubricant distribution, thus avoiding common gear failure modes. Furthermore, inertia matching is another key advantage of planetary gearboxes for optimizing motion design. Matching the load inertia to the motor rotor inertia enables a cost-effective and easily controllable design.

While a “perfect” 1:1 inertia ratio is impractical in many cases, most servo system designs aim to minimize the inertia ratio as much as possible to achieve high system response speeds. Reducing load inertia by adding a gearbox to the system means a smaller motor (with lower inertia) can be used while still maintaining the ideal ratio between the motor and the load.

A ratio greater than 1:1 usually requires a larger motor and controller, while a ratio less than 1:1 indicates an oversized motor—where the torque used to drive its own rotor is greater than that used to drive the load. Planetary gearboxes provide engineers with a way to balance design costs and performance.

Arguably the most important advantage of using a gearbox in a servo system is its impact on load inertia. Load inertia is transmitted to the motor and reduced by the square of the gear ratio. Therefore, even a relatively small gear reduction ratio can have a significant impact on the inertia ratio.

Most servo mechanism sizing guidelines recommend an empirical inertia ratio of 10:1 or lower. In practice, however, the “optimal” inertia ratio depends on the specific application: for applications with a wide dynamic range and high precision, the ratio may be less than 10:1; for applications with high feedback resolution and fast response speeds (where rapid error correction is needed to avoid system instability), the ratio may be much higher than 10:1.

J L = Load inertia reflected to the motor

J M = Motor inertia

J D = Inertia of the drive device (screws, belts and pulleys, or actuators)

J E = Inertia of the external (moving) mass

J C = Coupling inertia

J G = Gearbox inertia

i = Gear ratio

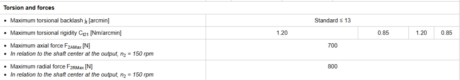

It should be noted that all planetary gearboxes have extremely low backlash, but different grades still exist. If the additional cost of an ultra-precision gearbox (with backlash of just a few arcminutes or less) is prohibitive, gearboxes with 10 or even 20 arcminutes of backlash can be selected.

When seeking assistance from a planetary gearbox manufacturer, engineers are more likely to obtain a gearbox that fits correctly and performs to specifications if they review and answer the following questions as thoroughly as possible:

- What are the input speed and torque?

- What is the target output speed or torque of the gearbox? This partially determines the required gear ratio.

- What are the operating characteristics of the application? How many hours per day will the gearbox run? Does it need to withstand shock and vibration?

- What is the overhang of the load? Are there internal overhang loads? Note that bevel gears usually cannot be equipped with multiple support bearings because their axes intersect, so one or more gears often operate in an overhanging configuration.

After sizing is determined, the manufacturer’s catalog or website will list the maximum allowable overhang load for that size of gearbox. Tip: If the load in the application exceeds the allowable value, the gearbox size should be increased to withstand the overhang load.

Such loads cause shaft deflection, leading to misaligned gear meshing, which in turn reduces tooth contact quality and service life. A potential improvement is to use straddle-mounted (opposed) bearings on both sides of the gear for support.

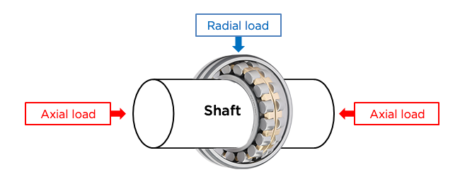

- Radial and axial loads (must be considered): Although gearboxes are usually equipped with large output bearings, factors such as belt tension, misalignment, gravity, or thrust acting on the output shaft should still be considered. Compare requirements with the gearbox specifications, and use external support bearings if necessary.

- Radial loads: Forces acting perpendicular to the output shaft (e.g., belt tension, chain pull, pinion weight).

- Axial loads: Forces acting parallel to the output shaft axis, representing thrust loads.

Radial and axial loads refer to the maximum radial and axial forces acting on the output shaft. These loads come from transmission components mounted on the output shaft, such as sprockets, pulleys, timing belts, gears, and other drive elements.

Radial and axial loads are closely related to the strength and rigidity of the gearbox output shaft, bearings, gears, and the gearbox itself. Overloading may damage the gearbox and its components.

Axial loads, also known as thrust loads, are forces applied along the axis of a mechanical component or bearing. They cause the component to move along the axis, toward or away from the force source. Pushing or pulling a component along a straight line is the simplest example of an axial load.

Radial loads are forces applied perpendicular to the axis of a mechanical component or bearing. Acting perpendicular to the axis, they aim to cause radial compression or deformation of the component. The force exerted on a wheel as it rolls on a surface is an example of a radial load.

- Does the machine require a shaft or hollow bore input, or a shaft or hollow bore output?

- What is the mounting orientation of the gear drive? For example, if using a right-angle worm gear reducer, is the worm located above or below the gear? Does the shaft extend horizontally or vertically from the machine?

- Does the environment require corrosion-resistant paint or stainless steel housings and shafts?

- Service factor: Most gearbox manufacturers first determine a service factor. This factor adjusts for variables such as input type, daily operating hours, and potential shock or vibration in the application.

For example, applications with irregular shocks (e.g., grinding applications) require a higher service factor than those with uniform loads. Similarly, gearboxes operating intermittently require a lower service factor than those running 24 hours a day.

-

Service class: After determining the service factor, the next step for engineers is to define the service class. For instance, a gearbox paired with a standard AC motor, driving a conveyor with uniform load and constant speed for 20 hours a day, may have a service class of 2.

-

Mounting: At this point, the designer or manufacturer has determined the gearbox size and performance. The next step is to select the mounting method. There are many common mounting configurations, and gearbox manufacturers offer multiple options for each gearbox size.

-

Lubricants, seals, and motor integration: After determining the unit size and configuration, several specific details need to be confirmed. Most manufacturers can deliver gearboxes pre-filled with lubricant; however, most ship gearboxes without lubricant by default to allow on-site filling by the user.

For applications with vertical shafts, some manufacturers recommend using a second set of seals. Finally, since many gearboxes are ultimately mounted to C-frame motors, many manufacturers also offer a service to integrate the motor into the gearbox and deliver the entire assembly as a single unit.